DOC KELLEY

(and Coquito)

Doc is the co-founder and Director of Operations at Psychedelic Sangha LLC. He is also a Buddhist scholar-practitioner who teaches in the Religious Studies Program at Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts at The New School in New York City.

Doc holds a Ph.D. and M.A. in Religion (Buddhist Studies) from Columbia University, where he studied under Dr. Robert Thurman. His academic and teaching expertise spans Tibetan Buddhism, Buddhist ethics, and experimental mysticism.

Beyond academia, Doc is a creative force who blends Buddhist philosophy with avant-garde art and performance. In 2018, he directed "FluxBuddha," a performance art concert at the Rubin Museum. He is currently collaborating with various musicians and visual artists on a series of live and recorded immersive Dharma Art experiences dubbed "Sonic Sadhana" (i.e., Bardo Bath, Vibing Vajrasattva, and Chöd).

Please take a look at his curriculum vitae for a concise account of his professional experience. And below is the start of a spiritual biography in prose.

MEETING THE DHARMA

& PSYCHEDELICS

Buddhism has been a part of my life for nearly as long as I can remember. I formally took refuge in 1998 at Kopan Monastery in Kathmandu (Nepal), but my Aunt Merry Colony exposed me to the Buddha Dharma when I was a child. I have fond memories of her performing exquisite Buddhist rituals and mind-altering meditations. Merry used to tell me far-out stories about her life in Nepal with her gurus Lama Zopa and Lama Yeshe. She gave me a wall poster with a Tibetan rendering of the bodhisattva Manjushri, a Buddhist deity who wields a blazing sword of wisdom that cuts through the darkness of ignorance—OM-A-RA-PA-TSA-NA-DHIH! Merry wrote this mantra of Manjushri in two-inch large sharpie lettering at the bottom of the poster and told me that if I recited it every day, then I would excel in my studies at school. I cannot attest to getting good grades, but I still say the mantra, and I have never been without an image of Manjushri in my home ever since.

I did not take a serious interest in Buddhism until I went to college and experienced two things—crisis and psychedelics. Through personal crisis I came to appreciate the Buddhist truth of duhkha, or “suffering.” Through psychedelics, I was able to get some experiential purchase on a feeling for the relativity of one’s identity that Buddhists frame in terms of anatman, or “no-self.“

My first psychedelic experience was earth-shattering for me, but not unlike the many trip reports of “ego death,” including that of Richard Albert (Ram Dass). And like all those psychedelic elders who passed through what Erik Davis aptly dubbed “the paisley gate,” my ego death experience became my closest experiential point of reference for the emptiness of self and nonduality in my new spiritual life as an American Buddhist convert. And with this new life, I buried my psychedelic yearnings in the closet and closed that gate! However, when I eventually received my bodhisattva vows, I made sure to whisper the caveat, “psychedelics were not in violation!” as I formally received them inside the temple of Gyalrong College at Sermey Monastery in South India.

That’s me watching my Aunty Merry Colony make mandala offerings when I was a boy.

After graduating from college in 1997, my mother gifted me a trip to Asia to visit Merry where she was living in Kathmandu. I arrived amidst the sacred anarchy of the Holi Festival that— like a psychedelic trip itself—challenged my everyday presuppositions about “normal” and triggered a cathartic culture shock. What I had planned on being a one-month sojourn in various Asian countries, turned into a year-long residency in Nepal, with two pilgrimages into Tibet by way of public bus and hired cars. After completing the Buddhist intensive known as the “November course” at Kopan Monastery, I took Buddhist Refuge Vows with Khensur Rinpoche Lama Lhundrup and consummated my life-long connection to Buddhism.

When I finally returned to USA, I took a job working at the FPMT International Office in Soquel, California where I knew I would meet new teachers, be able to continue my study of Buddhism, and hopefully earn enough money to go back to Asia. During my stint at the International Office, I was interviewed for a feature article in Mandala Magazine entitled, “The New Generation of Young Buddhist Practitioners.” The article is now twenty years old, but it still conveys the somewhat controversial view that I maintain regarding Buddhism and psychedelics:

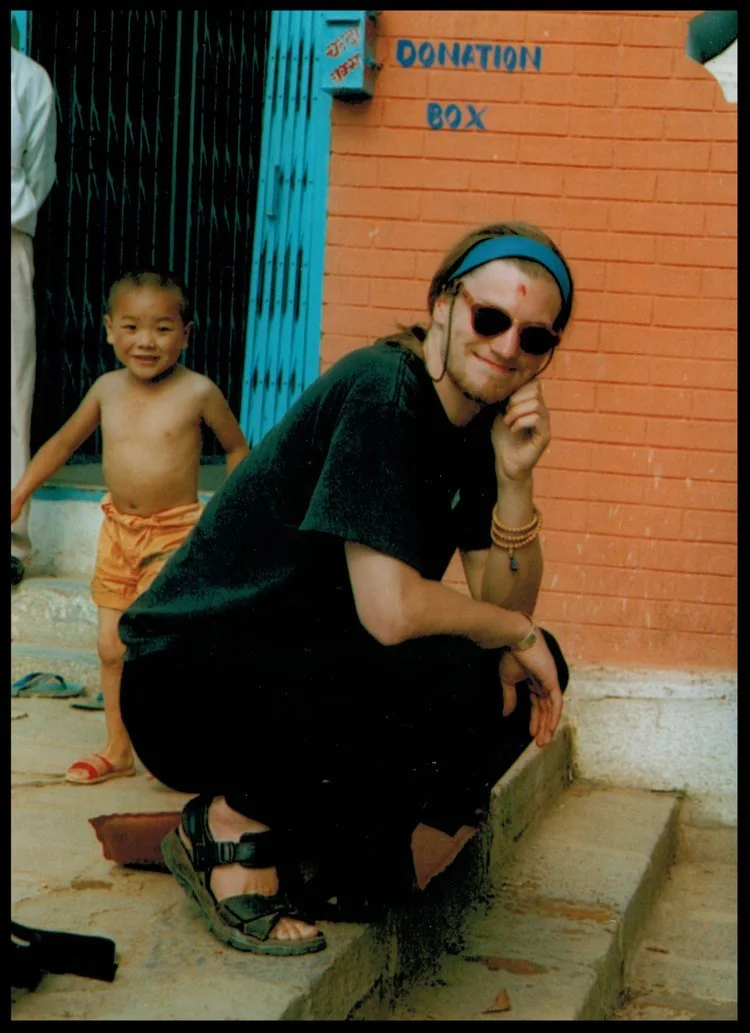

Falling in love with Kathmandu. And that’s a cheeky young Cherok Lama in the background (circa 1997).

I don’t think the true essence of Buddhism became accessible to me until after I had begun to experiment with hallucinogenic drugs.

I found that, through certain hallucinatory experiences, I was better able to understand my mind and specifically the way I had been perceiving reality. The change was that I had become more open to different views and philosophies on an experiential level.

I am not advocating casual drug use, but for myself, I think that there were certain experiences that I had, under the influence of drugs, that helped me to be more open to Buddhist thought and practice. And it was through these experiences that I found myself able to move on to a more real, drug-free experience.

It is widely known that many Americans discovered Buddhism by way of a transformative experience facilitated by a psychedelic substance—the “Paisley Gate” between hippiedom and Buddhism. As a result, there is general acceptance, within the American Buddhist community, of psychedelics as a gateway to more serious practice. According to some statistical research, there is a much higher percentage of people who have used psychedelics within American Buddhism than in the general population (see Osto). Speaking for myself, psychedelics were transformative and clearly had a lot to do with my renewed interest in Buddhism after college. Nevertheless, for many years I held my “sublime trauma” without really understanding that I needed help integrating it into my Buddhist life. It is immensely gratifying to see new research studies that strongly suggest, if not confirm, the power of psychedelics to open your mind and facilitate bonafide religious or mystical insight. It is largely a result of such research that we now have the emergence of “harm reduction” and “psychedelic education.” I encourage contemporary Buddhists to embrace the research and make strides to incorporate harm reduction and psychedelic education into our American Buddhist tradition.

I had the opportunity to meet several Buddhist teachers while working at FPMT International. One of those teachers was Geshe Michael Roach.

SERA MONASTERY

Like a lot of people in the American Buddhist scene, I was profoundly moved by Geshe Michael’s acumen and uncanny ability to translate the monastic curricula into a practical program of study for westerners. When I requested that he take me as a student, he wasted no time in sending me back to Asia. In less than three months after meeting him, I found myself on a plane headed to India to rendezvous with him at his own alma mater, Sera Mey Monastery in Bylakuppe.

I lived and ate meals with this family of monks everyday for about two years. I am eternally grateful to Geshe Lothar (far left), nephew of Sermey Khensur Lobsang Tharchin Rinpoche, who took me in and treated me with kindness, respect, and love (1998)

When Geshe Michael sent me to India, he said I would cherish the experience for the rest of my life—he was right. The monks I met are among some of the most beautiful souls I have ever known. They taught me Buddhism and how to live a simple and communal life. The fraternal and jocular culture of a Tibetan monastery was familiar to me; I had attended an all boys private school and was a high school and college athlete. It was easy for me to forget that I stood out among the maroon clad Tibetan monks. Nonetheless, monasticism was not my calling. And so after a few years in the monastery, I returned to my native home of New York where I met my future wife and decided to apply to graduate school at Columbia University.

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

At Columbia, I studied Tibetan Buddhism with Robert A. F. Thurman and Sanskrit with Gary Tubb. I learned the theory and method of religious studies as well as how to write a dissertation. In 2006 my wife and I had a child and we began the herculean task of raising one in New York City. My wife, a writer at the time, was just finishing work on her first book, The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America (Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2010). And I was exploring new areas of inquiry in consciousness studies and comparative philosophy.

In 2006, I received a grant to produce a two-day international symposium with twenty-four remarkable scholars from fields as diverse as neuroscience and Sanskrit literature. The event was called Mind & Reality, and it was convened in the historic Low Rotunda of Columbia University to discuss the "problem of consciousness." Needless to say, we did not solve the problem. The event, however, ignited a genuine interdisciplinary collaboration which led me to co-found a new University Seminar on comparative philosophy.

With faculty leadership from Professor Tubb, I co-founded University Seminar #721: The Columbia Society for Comparative Philosophy (CSCP). I organized several meetings for CSCP as well as another conference on the nature consciousness, The Reflective Self. For this event we narrowed the scope and adopted a more phenomenological approach.

In 2010 my second daughter arrived, and I began my teaching career. I was among a few graduate students who were selected to teach Literature & Humanities in the Core Curriculum of Columbia College. Though the syllabus was largely comprised of western texts, there was room to supplement with some non-western masterpieces like Ashvaghosha’s Buddhacharita (Life of Buddha). I relished the opportunity to teach the classics and take part in the tradition of teaching the great books of western civilizations.

Teaching Lit Hum on a beautiful fall morning on the campus of Columbia University.

My dissertation was also beginning to emerge, and I discovered my passion for western ethics and moral philosophy. And most especially, the project of understanding Buddhism through that lens. This led me to convene another large scale academic conference, but this time it was dedicated to the topic of Buddhist ethics and moral philosophy.

And so in 2011, I won a grant from The John Templeton Foundation to develop Contemporary Perspective on Buddhist Ethics— the first academic conference solely devoted to the topic of Buddhist ethics and moral philosophy. And thanks to my co-organizer Dr. Jake Davis, we were able to publish a volume of the conference papers (including one of my own) under the title, A Mirror Is for Reflection: Understanding Buddhist Ethics (Oxford University Press, 2017).

During this period, I found myself asking penetrating questions about western ethics and Buddhism—does Buddhism have a discernible normative theory of ethics? And if so, does it resemble any of those in western philosophy? Does Buddhism have a concept of human rights that is similar to the one put forth in seminal documents like The American Declaration of Independence and The Universal Declaration of Human Rights? After all, the Dalai Lama is an outspoken proponent of the UDHR. Nevertheless, he is also—first and foremost—an advocate of the anti-essentialist Middle Way school of Buddhist philosophy. Can we reconcile ideas like “inherent dignity” and “inalienable rights” with the Middle Way view that all things lack intrinsic nature? The result was my dissertation Toward a Buddhist Philosophy and Practice of Human Rights, where I argue that Middle Way school, like western postmodern deconstructionism, is indeed not compatible with the Kantian understanding of rights as ontologically inherent and inalienable. However, unlike western post-modernism, the Middle Way offers human rights philosophy a robust defense. Not to mention some very useful introspective tools for actualizing rights beyond their philosophical import.

After graduate school I took a part-time teaching position in the religious studies program at Eugene Lang College, The New School. I was hired to teach “Religions of South Asia,” but soon I was creating original interdisciplinary courses of my own design like: “Buddhism and Human Rights,” “Mind & Matter in Indian Philosophy,” “Buddhism and Cognitive Science,” as well as reinventing traditional introductory courses on Hinduism and Buddhism.

CONSCIOUSNESS HACKING

As I previously mentioned, I am with Rorty who asserts that the function of abnormal discourse, and by extension education in general, is to “take us out of our old selves by the power of strangeness, to aid us in the becoming of new beings.” I value discourse that pushes the boundaries of “normal” or accepted disciplinary conventions. And so I did not hesitate to accept an invitation to co-found the New York chapter of a new science and technology movement called, Consciousness Hacking.

“Consciousness hacking” is a neologism that was coined by technologist Mikey Siegel to refer to the act of subverting preexisting outer technologies toward an inner spiritual aim like enlightenment (i.e. biofeedback devices for quantifying meditative states). Together with my business parter Spiros Antonopoulos, and then later with Todd Gailun, we grew our Consciousness Hacking - NYC public Meetup group to nearly 3000 members in two years. We hosted a wide variety of speakers and artists, workshops, and tech demonstrations. We convened monthly meetings at The New School, NYU, The Alchemist’s Kitchen, and Eddie Stern’s yoga shala. Our largest event was a four-day Consciousness Hacking Film Festival at the Rubin Museum of Art that featured mind-altering films and a special session led by Mikey Siegel himself. Consciousness hacking may be a new movement, but in the bigger historical picture it is simply the most recent manifestation of a perennial human predilection to alter one’s consciousness toward a spiritual aim.

Through consciousness hacking I rediscovered psychedelics and was pleased to find that there was new research being done on their therapeutic efficacy. Michael Pollan’s groundbreaking New Yorker article, “The Trip Treatment,” trumpeted a new wave of psychedelic research— a “psychedelic renaissance”— happening in laboratories at John’s Hopkins University, NYU, and various other institutions of higher learning in Europe. Pollan’s article introduced me to the work of Drs. William Richards, Katherine MacLean, and Roland Griffiths, et. al., who were looking into the role of psychedelics vis-a-vis mystical experience. I found their scientific findings jibed with my own subjective experience. Emboldened by this newfound legitimacy of the therapeutic value of psychedelics, I began to add journal articles and papers on psychedelic science to my syllabus for “Buddhism and Cognitive Science.” It has always been clear to me that the philosophical ideas and contemplative technologies of Buddhism provide a perfect container for utilizing the spiritual potential of psychedelics (i.e. “set and setting”). My students responded very positively to the new readings and the conceptual pairing of contemplative and psychedelics sciences. This early “honeymoon” stage of the psychedelic renaissance was very exciting for intellectuals, such as myself, who had closeted aspirations to explore psychedelics as tools for spiritual evolution. It was with unbridled enthusiasm that I agreed to sit down for an interview with Madison Margolin, a reporter for the The Village Voice who was writing a timely article on the emerging new psychedelic frontier.

COMING OUT OF

THE PSYCHEDELIC CLOSET

I met Ms. Margolin at the New School where we talked for a couple hours in my office. I found myself opening up and going on the record (again) about my own psychedelic experience and controversial views on their potential to facilitate mystical or religious insight. It was a lovely conversation that—later that night—I worried was too forthcoming. In the days following that interview, I wrestled with my fear of repercussions—both socially and professionally. Eventually I met my fear and decided to embrace it. I would own my psychedelic past and not shy away from being honest and forthright about my views regarding their soteriological efficacy. Madison wrote up the piece, but her editor at the Voice scraped the article at the last minute, and so it was never published. From my perspective it no longer mattered—I was psychologically “out of the psychedelic closet” (even if nobody knew it yet). a

The American Buddhist tradition is generally very tolerant of psychedelic use as a gateway to Buddhism, but intolerant of continued psychedelic use beyond the Paisley Gate. Buddhists usually do not consider psychedelic drugs a legitimate or effective tool for enlightenment.

Officially “coming out” of the “psychedelic closet” at the University of Pennsylvania (2015).