Jigoku: Buddhist Hell in Japanese Cinema

[Content advisory: graphic images and strong Buddhist themes.]

My initial reasons for writing about the 1960 cult classic Japanese horror film, Jigoku (“Hell”), were straightforward: it’s a good choice for the Halloween season, the titular hell is a Buddhist hell (the “Eight Hells,” actually), and the scenes in the underworld are really trippy. Plus, I liked the idea of confronting what may be an awkward topic for many secular Buddhists, who prefer to think of Buddhism as more of a philosophy than a religion—or a more evolved and rational religion, at least—well beyond such seemingly Judeo-Christian atrocities of the imagination as eternal damnation. Western supernatural horror movies are so very, very Catholic, taking place in a nightmare universe far removed from our visions of radiant, bejeweled buddha-fields. But, as scholar Jens Braarvig has put it, “our sources for the idea of hell in Buddhism are very rich.” Or to quote Professor Yajima, the fictional scholar who opens Jigoku with an expository lecture on concepts of hell, “In fact, the number of sutras on the subject is enormous.” The rabbit hole to Buddhist hell runs deep—I wasn’t prepared.

Frankly, the plot of Jigoku isn’t important. About an hour in, all the characters die and go to the Eight Hells. That’s all anyone talks about, and it’s worth the price of admission (in this case, a $10.99 per month subscription to the Criterion Channel). The last forty or so minutes of the film are an orgy of ‘60s, B-movie gore, as everyone is tortured and dismembered by demonic “hell wardens.” Director Nobuo Nakagawa and screenwriter Ichiro Miyagawa take an old formula of Japanese moviemaking—ero-guro-nansensu (“erotic-grotesque-nonsense”)—to a Sadean extreme. In a 2006 interview, Miyagawa cites several sources of inspiration: Goethe’s Faust, Hollywood movies, his own childhood memories of temple murals depicting hell, and ezoshi (“picture book”) reprints of medieval “hell scroll” paintings. He insists that Jigoku isn’t depicting physical torture, but rather psychological suffering expressed in images.

Oddly, Miyagawa doesn’t mention the Ōjōyōshū (“The Essentials of Rebirth in a Pure Land”), a tenth-century text by the Tendai Buddhist Master Genshin, which is clearly the biggest influence on Jigoku’s phantasmagoric finale. The cosmology of eight levels or departments of hell can be traced all the way back to the Kathāvatthu, the earliest Buddhist scripture with a named author, composed by “the Elder Mogalliputtatissa” sometime between 250 and 100 BC, according to the Pāli tradition. (Actually, there are at least sixteen levels of hell—“eight hot hells” and “eight cold hells”—but the cold hells are minor hells, mentioned only in passing by both Genshin and Jigoku.) Vasubandhu’s Verses on the Treasury of Abhidharma, from the 4th or 5th century, is a key text, too. But it was Genshin’s elaboration upon this infernal layout, with its graphic description of the punishments specific to each level, which cemented the Eight Hells in the Japanese imagination. From top to bottom, in Sanskrit (and Japanese), the Eight Hells of the Ōjōyōshu are:

Samjīva (Tôkatsu jigoku), the “Hell of Revival”;

Kālasūtra (Kokujô jigoku), the “Hell of Black Ropes”;

Samghāta (Shugô jigoku), the “Hell of Assembly”;

Raurava (Gōkyō jigoku), the “Hell of Screams”;

Mahāraurava (Daikyô jigoku), the “Great Hell of Screams”;

Tāpana (Ennetsu jigoku), the “Hell of Incineration”;

Pratāpana (Dainetsu jigoku), the “Great Hell of Incineration”;

Avīci (Muken jigoku), the “Hell of No Interval.”

From Buddhist Cosmology: Philosophy and Origins, by Akira Sadakata. (Distances and dimensions measured in yojanas.)

Traditionally, each evildoer is sentenced to one of these specific hells, according to their offenses. But with Jigoku, according to screenwriter Miyagawa, the “whole of hell was meant to be shown in the film.” The main character, Shirô, runs “through all kinds of hells.” In other words, the filmmakers had to squeeze all Eight Hells into forty minutes, and Jigoku’s finale is a jumble of images adapted (some faithfully, some loosely) from the Ōjōyōshu:

“ ... the sinners are put into an iron caldron and boiled like one boils beans ... ”

“ ... feet are lacerated by sharp swords with which the road is studded as thickly as growing grass ... ”

“ ... after marking them with hot iron cords in both directions as a carpenter makes marks with his line, they cut them up into pieces with hot iron axes, following the markings ... ”

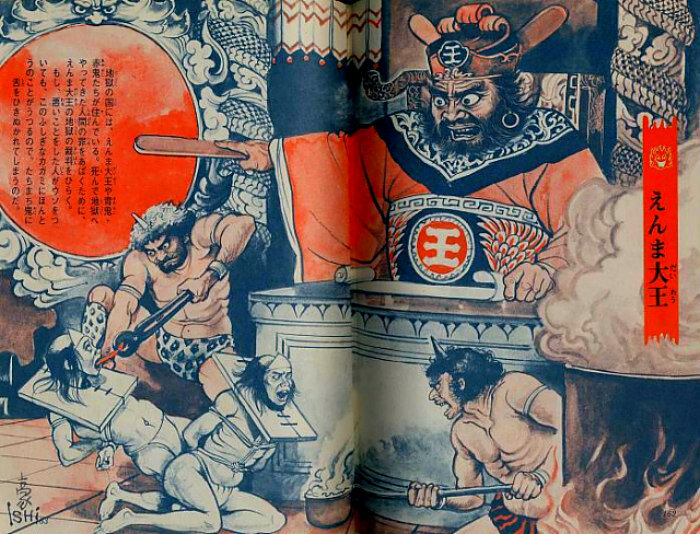

While digging around the internet, I discovered this series of paintings by an unnamed contemporary artist—almost impressive, in their fidelty to Genshin’s descriptions. (Somebody is really into the Ōjōyōshu.) Check out this one, which depicts Enma, the King of Hell, along with the “ox-headed and horse-headed” wardens of the third hell, Samghāta. In the lower left corner, BoJack Horseman flogs a sinner.

As far as I’m concerned, Enma (also known as Emma-O) is the most interesting character in Jigoku, even though he’s onscreen for only a few seconds. The movie gets the details right: the robes of a magistrate, a crown or bonnet bearing the Chinese character for “king,” and a fierce red face with protruding canine teeth.

As just noted, he’s King of Hell. He’s also the Judge of the Dead. Before passing judgment, Enma forces each sinner to gaze into an “all-revealing mirror” which replays their multitude of karmic crimes.

Enma is an East Asian variation on Yama, who can be traced back to the Vedas of ancient India. Yama’s stats are decent, for a demigod:

From Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Deities & Demigods, by James M. Ward, with Robert J. Kuntz.

To follow Yama’s “career” or trajectory is also to trace the development of karma as a concept. According to Jens Braarvig, karma begins with the sacrificial cult of Yama, who was the first man, the “Adam” of the Vedas. Being the first man, Yama was also the first man to die—a trailblazer to oblivion, if you will. He was the first to arrive at the abode of the dead—a heavenly paradise—and he claimed it as his kingdom. Originally, karma denoted resources which were sacrificed by living descendants of the deceased. For the ancestors to enjoy their afterlife, the living had to provide for them, by offering material compensation on their behalf. Over time, karma became less material and more abstract, developing into an ethical concept of reward or retribution for one’s conduct in life. As the meaning of karma shifted, the world of revered ancestors became the punitive afterlife of hell, and Yama “descended” from his role as “king of the forefathers” into a new role, as the ruler of the underworld. According to Akira Sadakata, “As we examine how Yama made his downward journey, we trace the development of the Buddhist idea of hell.”

What’s more, Yama’s story helps reveal a big difference between Buddhist and Judeo-Christian cosmology: hell is not eternal; hell is simply one of many forms of rebirth. For even King Yama was reborn in the lowest and worst realm because of his own actions; he’s not the eternal ruler of hell, he’s simply a transmigrating being like the rest of us, and just as subject to the law of karma. The same goes for the wardens of hell, too. Typically, Buddhism describes six “paths of transmigration” or “realms of sentient experience” (gati), a karmic ladder running from the gods (devas) down to demigods (asuras), humans, animals, hungry ghosts, and the “inhabitants of hell.” (Some early, Pāli canon accounts omit the asuras and list only five realms. Other, Mahāyāna accounts expand the list to ten realms by adding śrāvakas, pratyekabuddhas, bodhisattvas, and buddhas to the top tiers, above the gods). So Buddhist hell is not a one-way ticket, is not a final dumping ground for the souls of sinners (obviously, since there is no soul in Buddhism). It’s a form of life, a “realm” into which one is reborn, due to the effects of bad (really bad) karma. It’s more accurate to call Buddhist hell “purgatory” or “perdition”—even if the punishments or “terms of life” in these purgatories can go on for centuries, millennia, or even eons. If there is a hell, it’s all six of the realms—it’s samsāra, the wheel of birth-death-rebirth.

Jigoku, however, never gives any indication that its nightmare is just temporary (except maybe—maybe—some ambiguous imagery in the very last shots of the film, which some have interpreted as symbolizing peace and purity). The film seems uninterested in offering its characters or its audience any glimpses of hope or redemption. This hopelessness is reinforced by a conspicuous absence in its hell’s roster. After meeting Enma, we find ourselves along the banks of the River Sanzu (the Japanese equivalent of the River Styx or the River Acheron, i.e., “the border between life and death”). In the film, at least, the banks of the Sanzu are also Sai-no-kawara, the “riverbank of suffering”: we witness a group of spectral children (“held in limbo for having died before their parents”), building cairns or little stupas of pebbles as their penance. In Japanese folklore, the children must build these stupas without cease, as a Sisyphean task; every time a pile nears completion, a demonic guard knocks it down and forces the child to start over. However, the bodhisattva Ksitigarbha (Jizō in Japanese), widely revered as a compassionate “buddha in hell,” hears the cries of these children and comes to their aid. He plays with them, protects them from the demons, and helps them build their pebble mounds. He gently shepherds them out of limbo and toward the Pure Land. In some accounts, Yama/Enma is merely the fierce aspect of this kindly bodhisattva—all bark and no bite. But Jizō is nowhere to be seen in Jigoku. The children simply evaporate into darkness, leaving us with only their little stone stupas, and eery silence.

ψ संघ

Bonus content!

Here’s a few illustrations of Lord Enma and his hell-minions, by Gōjin Ishihara. They’re from The Illustrated Book of Japanese Monsters, which is a cult classic in its own right, published in 1972 as a picture book for children. Enjoy!

ψ संघ